The Genesis of Primary Health Care

The story of primary health care (PHC) isn’t one of sudden invention, but rather a gradual evolution of ideas and practices, stretching back to the early 20th century. Imagine a time when access to even basic medical care was a luxury for many, particularly in rural communities. Early initiatives, such as those supported by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1930s rural China, began to address this disparity. These programs, focused on bringing essential services directly to underserved populations, foreshadowed the core principles of PHC: community-based care, accessibility, and a focus on prevention. These pioneering efforts suggested that effective healthcare could be delivered outside traditional hospital settings, hinting at the potential of community-centric approaches.

Concurrent with these practical experiments, influential figures like John Grant and Andrija Štampar championed the concept of “social medicine.” They argued that health is inextricably linked to broader societal factors, encompassing agriculture, education, and socioeconomic conditions. This holistic perspective, recognizing that addressing the root causes of ill health within communities was just as vital as treating diseases, was a radical departure from the prevailing medical models of the time. Selska Gunn, another prominent voice, echoed this sentiment, emphasizing the interconnectedness of health with a person’s overall well-being. These early proponents helped shift the focus from simply treating illness to proactively creating healthier communities. The 1937 League of Nations Rural Hygiene Conference in Bandoeng, Indonesia, further reinforced this “intersectoral” approach, acknowledging the need to address the complex web of factors influencing health.

The Christian Medical Commission (CMC) added a crucial dimension to the evolving PHC narrative: social justice. The CMC advocated for community empowerment, recognizing that true health meant enabling communities to take ownership of their well-being. Their work highlighted the inseparable link between social justice and health equity, underscoring that access to healthcare is a fundamental human right.

By mid-century, figures like Sidney Kark, Rex Fendall, Maurice King, and Milton Roemer refined these burgeoning ideas. They developed practical models, such as community health centers and training programs for local health workers, which became integral components of modern PHC. These developments laid the groundwork for a more comprehensive and community-centered approach to healthcare delivery.

The Alma-Ata Declaration: A Watershed Moment

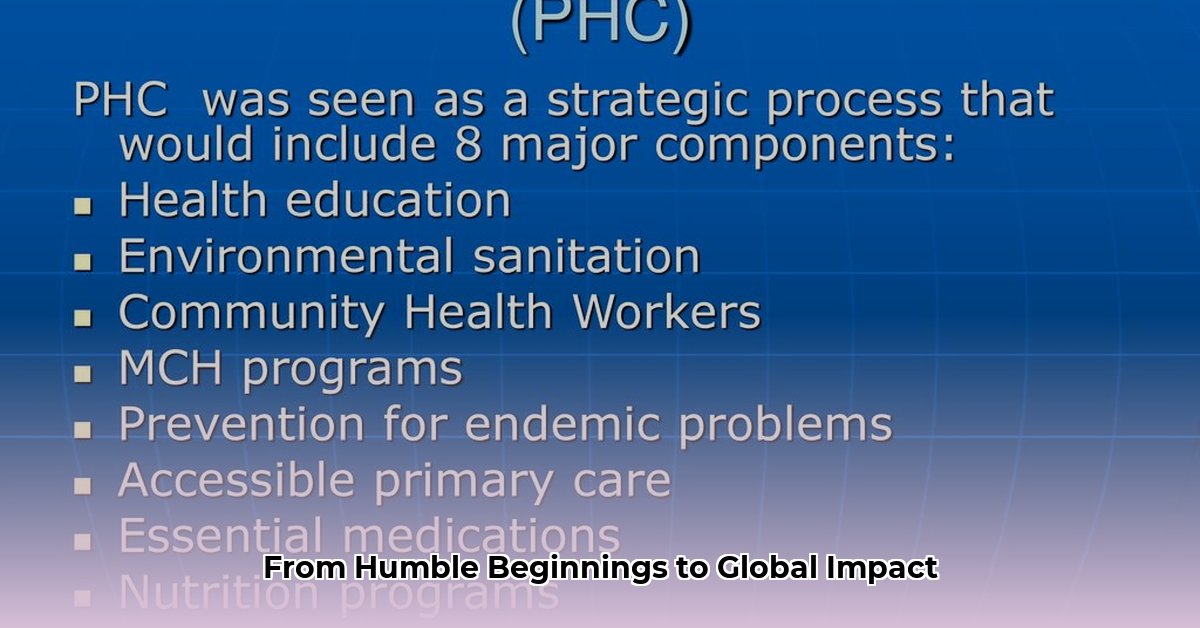

The year 1978 marked a watershed moment in global health: the Alma-Ata Declaration. This landmark declaration formally recognized PHC as the cornerstone of “Health for All,” enshrining decades of advocacy and innovative practice. The declaration’s emphasis on community participation, appropriate technology, and equitable resource distribution crystallized the evolving philosophy of PHC. It outlined eight essential components: health education, proper nutrition, safe water and sanitation, maternal and child health care (including family planning), immunization, prevention and control of endemic diseases, treatment of common diseases and injuries, and provision of essential drugs. But was it the definitive turning point? It’s a complex question.

While Alma-Ata undoubtedly galvanized the global PHC movement, its implementation has been far from straightforward. The subsequent emergence of “Selective Primary Health Care,” a more targeted approach prioritizing specific interventions, sparked ongoing debate. Some viewed this as a pragmatic response to resource constraints, while others argued that it compromised the holistic vision of Alma-Ata. This tension between comprehensive care and targeted interventions persists in contemporary PHC discussions. Further complicating matters, the “Health for All by 2000” goal, while aspirational, proved unattainable, underscoring the significant challenges in translating global declarations into tangible progress.

The Path Forward: PHC in the 21st Century

The journey of PHC continues to unfold in the 21st century, marked by both progress and ongoing challenges. The renewed emphasis on PHC as a foundation for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) signifies a reaffirmation of its core principles. This resurgence suggests a growing recognition that sustainable health improvements require addressing the social determinants of health, empowering individuals and communities, and building resilient health systems. The integration of technology offers promising avenues for enhancing PHC delivery, from telehealth to data-driven decision-making. However, persistent inequities in access, resource allocation, and quality of care remain significant hurdles.

Furthermore, evolving global health landscapes, including climate change, emerging infectious diseases, and aging populations, present new complexities for PHC. These challenges demand innovative solutions and adaptable strategies. Ongoing research and community-based initiatives are essential for navigating these evolving circumstances and ensuring that PHC remains relevant and effective in the decades to come. The history of PHC reminds us that the pursuit of health equity is an ongoing process, requiring continuous adaptation, collaboration, and a steadfast commitment to the principles of Alma-Ata.

Key Figures: The Architects of PHC

While the Alma-Ata Declaration stands as a pivotal moment, it represents the culmination of decades of work by dedicated individuals and organizations. These pioneers, often working in challenging circumstances, laid the conceptual and practical groundwork for PHC as we know it.

-

Early Innovators: The Rockefeller Foundation’s work in rural China demonstrated the feasibility and impact of community-based healthcare delivery, while the League of Nations Health Organization provided an early platform for international collaboration on health issues.

-

Champions of Social Medicine: Visionaries like John Grant, Andrija Štampar, and Selskar Gunn challenged conventional medical paradigms, advocating for a broader understanding of health that encompassed social, economic, and environmental factors.

-

Advocates for Community Empowerment: The Christian Medical Commission played a critical role in promoting community participation and ownership in healthcare, recognizing that sustainable improvements require empowering individuals and communities to take charge of their own well-being.

-

Field Pioneers: Individuals like Sidney Kark, Rex Fendall, Maurice King, and Milton Roemer developed and implemented practical models of PHC, demonstrating the effectiveness of community health centers, training local health workers, and integrating healthcare with other sectors.

These individuals, along with countless others working at the grassroots level, shaped the philosophy and practice of PHC, paving the way for the Alma-Ata Declaration and its enduring legacy.

The Evolution of PHC Principles

The principles of PHC, as articulated in the Alma-Ata Declaration, did not emerge fully formed. They represent the culmination of a long and complex historical process, shaped by diverse influences and ongoing debates.

-

Early Seeds of Change: The early 20th century witnessed a growing recognition of the limitations of hospital-centric healthcare models, particularly in reaching underserved populations. Initiatives in rural China and elsewhere demonstrated the potential of community-based care, emphasizing accessibility and prevention.

-

The Rise of Social Medicine: Influential thinkers challenged the prevailing medical paradigms, arguing that health is inextricably linked to social, economic, and environmental factors. This holistic perspective laid the groundwork for PHC’s emphasis on intersectoral collaboration and addressing the root causes of ill health.

-

The Alma-Ata Paradigm Shift: The 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration formalized these evolving principles, establishing PHC as the cornerstone of “Health for All.” The declaration’s emphasis on community participation, appropriate technology, and equitable resource distribution represented a fundamental shift in global health thinking.

-

Post-Alma-Ata Challenges and Adaptations: The post-Alma-Ata era witnessed both progress and setbacks. Resource constraints and political pressures led to the emergence of Selective Primary Health Care, sparking debates about its compatibility with the holistic vision of Alma-Ata.

-

The Resurgence of PHC: In recent years, PHC has experienced a renewed prominence, fueled by the growing movement for Universal Health Coverage (UHC). This resurgence reflects a growing understanding that strong PHC systems are essential for achieving health equity and addressing the complex health challenges of the 21st century.

The ongoing evolution of PHC principles highlights the dynamic nature of global health. As new challenges emerge, PHC must continue to adapt and innovate, while remaining grounded in its core values of equity, accessibility, and community empowerment.

- Sectioned Tupperware for Organized Meals and Snacks on the Go - March 7, 2026

- Meal Containers with Dividers Keep Foods Separate and Fresh - March 6, 2026

- Tupperware with Dividers Makes Entertaining Easy and Organized - March 5, 2026